- Site Analysis

- Longevity and Size

- Placement and Culture

- What to Look For and When to Plant Shade Trees

- Shade Tree Selection Guide

Shade trees are a staple of Southern landscapes and include a variety of species, forms and seasonal appeal. In the Southeastern U.S., shade trees are used most often to provide relief from the summer sun and heat. Additionally, shade trees can be utilized to channel summer breezes to desired locations, add monetary value to a property, define outdoor spaces, and improve landscape sustainability by reducing soil erosion, decreasing storm water flows, increasing rainwater infiltration and increasing wildlife habitat.

In urban and suburban landscapes, tree selection is typically based on two criteria: (1) fast growth to provide quick shade on sparse new home sites and (2) small to medium mature size to accommodate small lot sizes. Many trees are advertised as “fast growing,” yet mature size is not often advertised by the seller or inquired into by the buyer. Thus, fast growing, large trees can quickly overpower a small landscape in an urban setting. The following information will assist homeowners in making informed decisions when selecting fast growing shade trees for urban and suburban environments.

Site Analysis

The lesson to learn is “right plant – right place.” This means that a concerted effort is made to match the environmental and soil conditions for optimum growth of specific plants to the site conditions where they will be planted. The goal of plant selection is to couple the strengths of the site with the requirements of the tree. The above-ground environmental factors that most influence tree performance include sunlight (intensity and duration of exposure), precipitation and seasonal extremes in temperature. Below-ground factors include soil texture, structure, fertility, soil moisture and underground obstacles that impede root growth. In addition, man-made obstructions such as utility lines, rights-of-way and legal restrictions should be investigated. The best way to determine the health of your soil is to test it. You can order a soil test kit or visit your County Extension Office where personnel can assist you with your soil testing, soil test analysis interpretation and additional information.

Longevity and Size

Consider the longevity of trees when planning a landscape. Trees can be divided into two general categories: (1) long-lived, to be used as permanent shade trees and (2) short-lived, to be used only as temporary shade trees or screens. Short-lived trees will require greater maintenance and typically should not be planted near sheds, power lines and other structures that can be damaged by tree failure. Many fast growing trees also have aggressive root systems with numerous surface roots. Consequently, determine the mature size (width) of the tree and avoid planting the tree within that distance from septic tank drain lines or sewer lines. For example, baldcypress (Taxodium distichum) has a final mature width of 40–50 ft so you will want to plant it at least 40–50 ft from underground structures.

Table 2 can help you match the size of the area under consideration with the mature size of the tree. Space large shade trees at least one-half the distance of the mature canopy diameter from any structure or overhead obstruction.

Placement and Culture

The effect of a shade tree is maximized when it is planted on the western or eastern side of a building or area where additional shading is desired. Many times trees are planted on both sides of a building that receives afternoon sun. Depending on the ultimate size and arrangement, only one to a few trees may be required to provide shade for an entire structure or outdoor living space.

Thorough soil preparation speeds establishment and enhances plant growth. A large planting hole, two to three times the size of the root ball and with well-tilled backfill soil, will produce satisfactory results. Organic soil amendments placed in the planting hole will NOT produce a superior tree (although their use in annual and perennial beds is recommended). Research indicates that the best use of organic materials when planting trees is as mulch. Over time, mulch will decompose into the soil, adding much needed organic matter.

For best results, add organic matter or compost to the entire landscape prior to planting. Continue adding organic matter over the life of the landscape, especially if soil conditions are poor as is often the case for new home construction. As the landscape matures, additions of leaves from the shade trees and other organic matter will increase the percent organic matter in your soil and improve soils that accompany new construction.

Plant at the proper depth, avoid excessive packing of the fill-soil, water the tree in after planting and mulch with 2 in. of an organic material such as pine bark or 4 in. of pine straw. Trees should receive 2 tablespoons of a 12 to 16% nitrogen fertilizer (12-4-8 or 16-4-8) per 10 sq ft of root area. Do not apply large amounts of fertilizer until the trees are established, usually after the first year. After broadcasting the fertilizer evenly over the planting area under the crown of the tree, water it in.

The single best cultural requirement you can provide to a young tree is water during establishment. Establishment in the landscape is helped tremendously with as little at 40 gallons added over the first season after planting. Even though plants are growing and look established in summer, they will always benefit from water, regardless of size, during their lifetime in your landscape.

What to Look For and When to Plant Shade Trees

Shade trees are usually bought balled and burlapped (B & B), container-grown or bare-root. Table 1 shows the best time of year to plant. Notice that optimal planting dates occur when the plant has just entered dormancy or is in full dormancy. Planting trees when they are dormant reduces water loss and transplant shock. Despite no apparent shoot growth, dormant plants grow roots through the winter. This head start will result in a more established tree the following growing season.

When selecting a B & B tree, make sure the root ball is moist and has not been broken, and that the soil is not cracking. When buying container-grown trees, check to see if one root in the top third of the root ball is one-fifth the size of the base of the trunk and is circling two-thirds of the trunk. If so, you might want to avoid this tree because it is potbound and may have trouble becoming established in the landscape. If the root system is heavy in the container but the large root described above is not present then follow these simple steps to plant it.

- Disturb the root ball just prior to planting by making two to four vertical cuts into the root ball.

- Work out some of the root tangles and try to integrate them into the backfill soil used to plant the tree in the hole.

- For bare-root trees, check the root systems and avoid trees with roots that have been allowed to dry, those with blackened root tips, or those that have an inadequate root system.

- Keep all types of trees (especially bare-root) moist at all times (but not in standing water) and avoid direct sunlight if possible prior to planting. In the case of B & B and bare-root trees, the roots can be kept moist by “healing in” or covering the roots with moist sawdust or organic mulch.

Table 1. Optimal planting times for plants produced in three production systems.

| Type | Planting Window | Optimal Planting Time |

| Balled & Burlapped | Late fall, winter or early spring (while dormant) | Late fall |

| Container-grown | Year-round | Early to late fall |

| Bare-root | Winter and early spring | Late winter |

NOTE: Due to a wide variety of soil and environmental conditions in the state of Georgia, we do not provide growth rate data for these tree species. However, for local information please contact your local UGA Cooperative Extension office. Office locations and contact information can be found at https://extension.uga.edu/county-offices.html

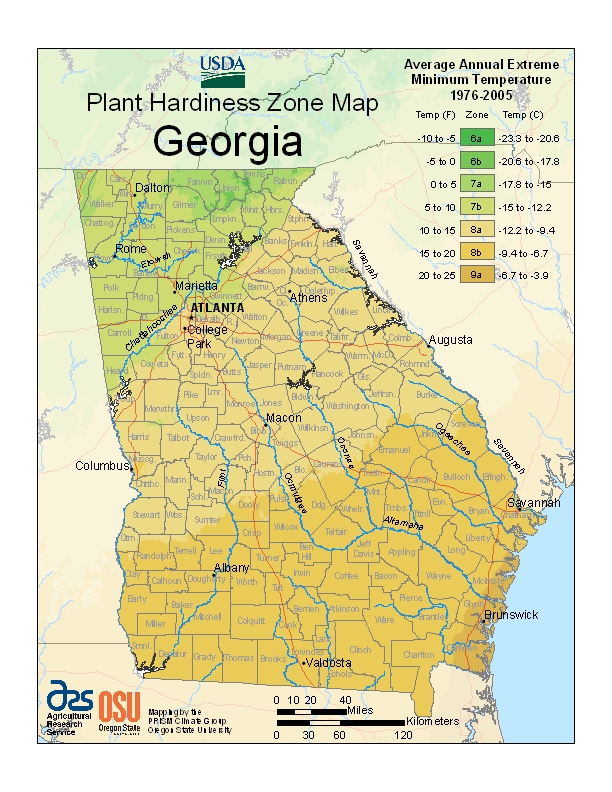

Figure 1. Plant hardiness zone map. Use this map along with Table 1 to determine if the tree you choose is hardy enough to withstand the average annual minimum temperature in your area.

Figure 1. Plant hardiness zone map. Use this map along with Table 1 to determine if the tree you choose is hardy enough to withstand the average annual minimum temperature in your area.Table 2. Shade Tree Selection Guide *

| Common Name/ Botanical Name |

Mature Height/ Canopy Diameter |

Good Fall Color |

Messy/ Requires Consistent Maintenance |

Flower (color) |

Distinctive Bark |

Tolerates Wet Soils |

Tolerates Dry Soils |

Use in Hardiness Zone(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Very Desirable

(Tolerates wide range of sites and/or possesses outstanding features.) |

||||||||

| Baldcypress / Taxodium distichum |

60-100’ /

40-50’ |

X

|

|

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

6,7,8

|

| Chinese dogwood / Cornus kousa |

20-30’ /

15-25’ |

X

|

|

White to

pink |

|

|

|

6,7,8

|

| Chinese fringe tree / Chionanthus retusus |

15-25’ /

15-20’ |

X

|

|

White

|

|

|

X

|

6,7,8

|

| Crape myrtle / Lagerstroemia indica x fauriei |

20-30’ /

15-25’ *Based on cultivar |

X

|

|

White to

red |

X

|

|

X

|

7,8

|

| Ginkgo / Ginkgo biloba |

35-50’ /

25-35’ |

X

|

|

|

X

|

|

X

|

6,7,8

|

| Northern red oak / Quercus rubra |

60-70’ /

50-60’ |

X

|

|

|

|

|

X

|

6,7

|

| Overcup oak / Quercus lyrata |

30-40’ /

30-40’ |

|

|

|

|

|

X

|

6,7,8

|

| River birch / Betula nigra |

50-60’ /

40-50’ |

|

X

|

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

6,7,8

|

| Sawtooth oak / Quercus acutissima |

50-60’ /

30-60’ |

|

|

|

|

|

X

|

6,7,8

|

| Scarlet oak / Quercus coccinea |

40-60’ /

35-55’ |

X

|

|

|

|

|

X

|

6,7,8

|

| Shumard oak / Quercus shumardii |

55-80’ /

50-60’ |

|

|

|

|

|

X

|

6,7,8

|

| Texas redbud / Cercis Canadensis var. texensis |

20-25’ /

15-20’ |

X

|

|

Lavender

|

|

|

X

|

6,7,8

|

| Trident maple / Acer buergerianum |

20-35’ /

20-35’ |

|

|

|

X

|

|

X

|

6,7,8

|

| Tulip poplar / Liriodendron tulipifera* |

80-100’ /

30-40’ |

X

|

X

|

|

|

|

|

6,7,8

|

| Willow oak / Quercus phellos |

40-60’ /

30-60’ |

|

|

|

|

X

|

|

6,7,8

|

| Zelkova / Zelkova serrata |

45-55’ /

35-45’ |

X

|

|

|

X

|

|

X

|

6,7,8

|

|

Good

(Best on good sites; might possess undesirable traits or pest problems.) |

||||||||

| Autumn blaze maple / Acer x freemanii |

45-55’ /

30-40’ |

X

|

|

|

|

X

|

|

6,7

|

| Boxelder / Acer negundo |

40-50’ /

25-35’ |

|

X

|

|

|

X

|

|

6,7

|

| Chinese lacebark elm / Ulmus parvifolia |

40-50’ /

35-50’ |

|

X

|

|

X

|

|

X

|

6,7,8

|

| Dawn redwood / Metasequoia glyptostrobodies |

70-90’ /

25-35’ |

|

|

|

X

|

X

|

|

6,7,8

|

| Eastern redbud / Cercis canadensis |

20-30’ /

15-25’ |

X

|

|

Lavender

or white |

|

|

X

|

6,7,8

|

| Golden weeping willow / Salix alba ‘Tristis’ |

30-40’ /

20-30’ |

|

X

|

|

|

X

|

|

6,7,8

|

| Goldenrain tree / Koelreuteria paniculata |

20-30’ /

10-15’ |

|

X

|

Yellow

|

|

|

|

6,7,8

|

| Green ash / Franxinus pennsylvania |

60-80’ /

40-50’ |

X

|

|

|

|

|

X

|

6,7,8

|

| Honeylocust / Gleditsia triacanthos var. inermis |

50-70’ /

35-50’ |

X

|

X

|

|

|

|

X

|

6

|

| Loblolly pine / Pinus taeda |

90-100’ /

20-40’ |

|

|

|

|

|

X

|

7,8

|

| Persimmon / Diospyros virginiana |

20-50’ /

15-30’ |

X

|

|

|

|

|

X

|

6,7,8

|

| Red maple / Acer rubrum |

40-60’ /

25-40’ |

X

|

|

|

|

X

|

|

6,7

|

| Red mulberry / Morus rubra |

50-70’ /

40-50’ |

|

|

|

|

|

X

|

6,7,8

|

| Sycamore / Platanus occidentalis |

80-100’ /

40-50’ |

|

X

|

|

X

|

X

|

|

6,7,8

|

| Weeping willow / Salix babylonica |

30-40’ /

20-30’ |

|

X

|

|

|

X

|

|

6,7,8

|

| White ash / Fraxinus americana |

75-100’ /

60-80’ |

X

|

|

|

|

|

|

6,7

|

| Yoshino cherry / Prunus x yedoensis |

20-30’ /

20-30’ |

X

|

|

Pink

|

X

|

|

|

6,7

|

|

Short-term solutions

(Possesses undesirable traits and/or pest problems. Use only as a temporary tree, if at all.) |

||||||||

| Southern catalpa / Catalpa bignonioides |

40-50’ /

25-35’ |

|

X

|

White

|

|

|

X

|

6,7,8

|

| Smooth sumac / Rhus glabra |

25-35’ /

30-35’ |

X

|

|

|

|

|

X

|

6,7,8

|

| Sweet gum / Liquidambar styraciflua |

80-100’ /

40-50’ |

X

|

X

|

|

|

X

|

X

|

6,7,8

|

| *This list of trees is based on the characteristics described in the table and the ability to commonly find these species in commerce. Many other species are worthy of consideration yet not readily available for purchase and therefore were omitted from this listing. | ||||||||

The authors thank James T. Midcap, Extension Horticulturist, and Neal Weatherly, Jr., College of Environmental Design for their input on the 1st Edition (1996) of this publication.