Photo: Emelie Swackhamer, Penn State University, Bugwood.org.

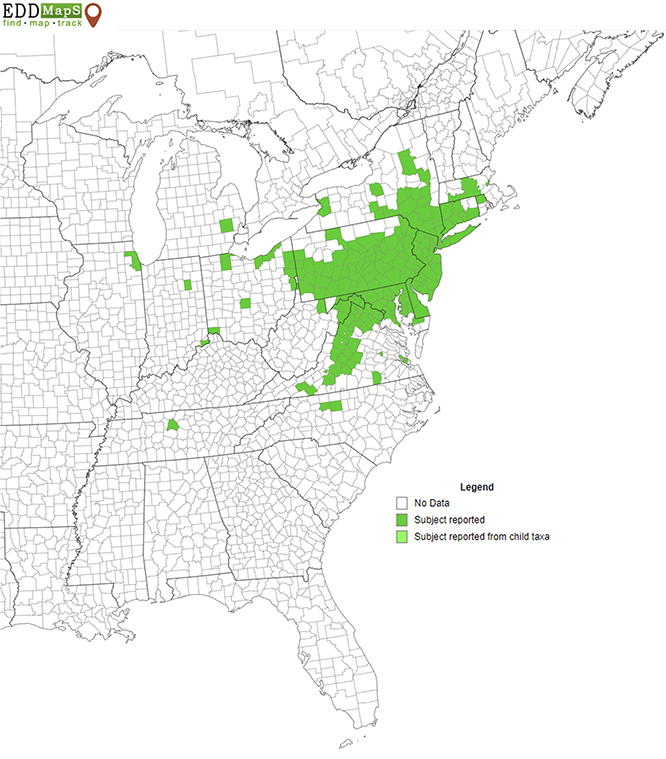

The spotted lanternfly (SLF; Figure 1), Lycorma delicatula (White), is an invasive planthopper that can feed on a wide range of trees in the United States. Spotted lanternflies are native to China, India, and Vietnam, and were first detected in Pennsylvania in September 2014. Since then, SLF has been confirmed in 17 other states: Connecticut, Delaware, Georgia, Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, Rhode Island, Tennessee, West Virginia, Wisconsin, and Virginia (Figure 2).

Map: Early Detection & Distribution Mapping System (EDDMapS), 2024, by the University of Georgia Center for Invasive Species and Ecosystem Health (https://www.eddmaps.org/).

In Georgia, the first recorded spotted lanternfly population was found in October 2024 in a residential yard in Fulton County. The potential economic and environmental impact of spotted lanternflies is alarming. In states where SLF is already established, the estimated value of grape and tree fruit industries is $915 million, and the ornamentals industry is valued at $2.6 billion. This threatens not only the livelihoods of many but also the biodiversity and beauty of our landscapes. This underscores the need for immediate action to prevent the spread of spotted lanternflies.

There is no evidence of SLF feeding directly on nursery stock, but notable indirect impacts can be found in ornamental nurseries. Nursery stocks should be free of all spotted lanternfly life stages before sale in the zones where SLF is established. This requires insecticidal treatment, which increases labor costs.

Damage

Spotted lanternflies are polyphagous (they can feed on various types of food) and can lay egg masses on various substrates (wood, rock, metal, etc.), so SLF can impact a broad range of industries. Adult spotted lanternflies emerge in late summer and aggregate (gather in large numbers) on host plants to feed. Using piercing-sucking mouthparts, spotted lanternflies take in nutrients from the plants.

Adults mostly feed on the trunks, whereas nymphs feed on the actively growing shoots. The presence of many adults feeding on a single tree (referred to as a “hot” tree) could result in heavy loss of phloem (the plant’s living tissue). Over time, this weakens trees and causes indirect effects, such as an increased susceptibility to drought, secondary pests, or pathogens.

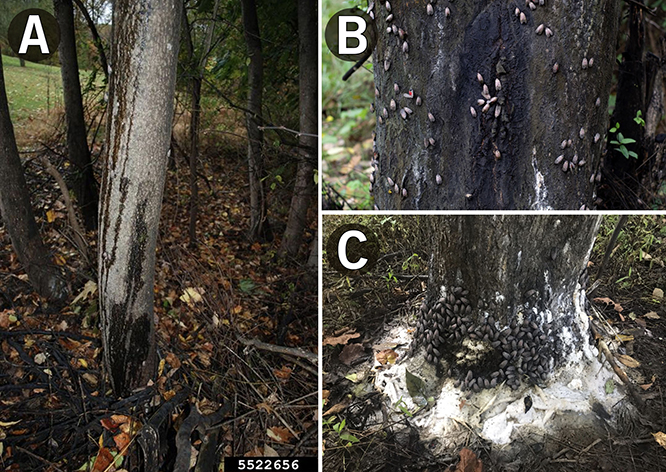

Photos: (A) Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture, Bugwood.org; (B) and (C), Daniel Barringer and Erin Smith, https://natlands.org/crows-nest-lanternfly-update/.

Adult feeding sometimes causes weeping bark as the sap oozes out of the trunk (Figure 3A). Adult spotted lanternflies ingest more sap than they need, which is excreted as a sugary substance called honeydew. They produce more honeydew than aphids or scales.

In some cases, honeydew falls as light rain from the tree canopy of infested trees. This honeydew attracts ants, bees, and wasps in the fall. Sooty mold fungus grows on honeydew, which blackens both tree trunks and any substrates beneath the spotted lanternflies (Figure 3B). Sometimes, the sugars in honeydew ferment with time, giving an unpleasant appearance (Figure 3C). The sooty mold growth and fermentation reduce the aesthetic value of not only the infested trees but also the general landscape where the affected trees are present.

Although trees rarely die from spotted lanternfly attacks, the pest exerts heavy stress on trees. When already under stress from biotic (disease or other insect infestation) and abiotic (e.g., drought) causes, the damage to SLF-infested trees is compounded. Severe yield reduction is observed in grapes because of spotted lanternfly infestation, and it can reduce the value of maples (silver and red) and black walnuts in the landscape.

Life Cycle

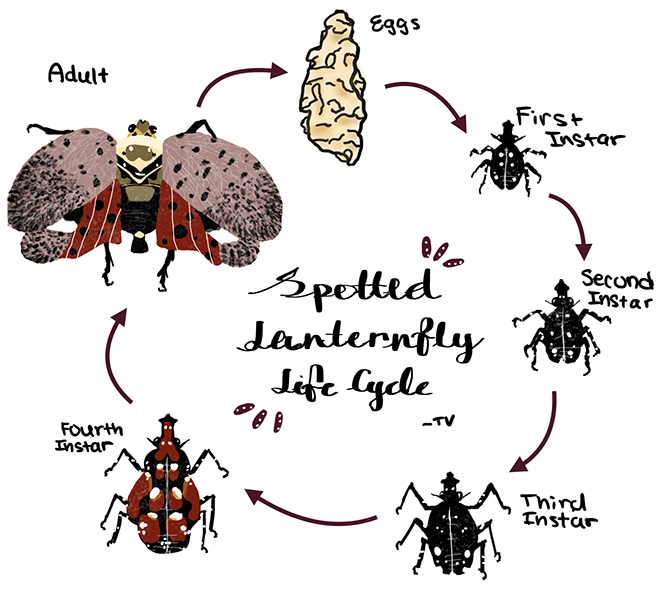

Illustration: Theresa Villanassery.

Spotted Lanternfly Eggs

In northern U.S. states, there is only one generation of spotted lanternfly per year. In the fall (September to October), mated females lay egg masses on the smooth surfaces of tree trunks and shrubs (Figure 4). Typically, eggs are found on the same host trees the adults feed on during the summer and fall. If host trees are not readily present, they can lay eggs on any structures they find, including fence posts, brick walls of buildings, vehicles, patio furniture, etc.

Photo: Richard Gardner, Bugwood.org.

Females coat their egg masses with a white substance, and as it dries, the egg masses look like mud patches or lichen growing on surfaces (Figure 5). Eggs are seed-like, brown-colored, and laid vertically. About 30–50 eggs are found in an egg mass, and a female can lay up to two egg masses in her lifetime. The eggs overwinter within the patch, and slowly, the patch withers away as it nears hatching in the spring of the following year (Figure 6).

Photo: Emelie Swackhamer, Penn State University, Bugwood.org.

Spotted Lanternfly Nymphs

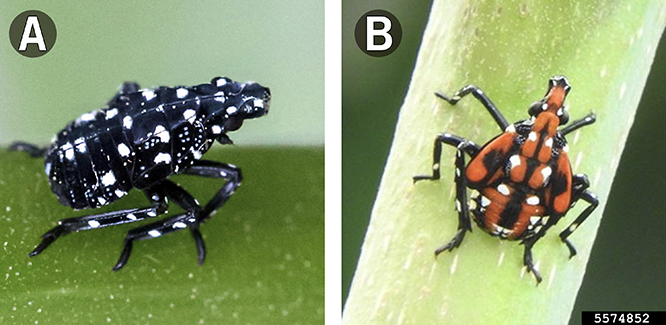

In northern states, eggs hatch in April and June, but hatching may come a little earlier in the southern states. Spotted lanternflies undergo four nymphal stages (instars) before molting into adults. The first (⅛ in. long), second, and third instars are black with white spots (Figure 7A). Their size increases as they molt at each stage. Fourth instars (½ in. long) are red with black and white spots (Figure 7B) and are often found alongside adults. Fourth instars molt into adults around August in northern U.S. states.

Photos: (A) Bill Keim, Pine Run Reservoir, Bucks County, Pennsylvania; (B) Richard Gardner, Bugwood.org.

Spotted Lanternfly Adults

An adult SLF measures 1 in. long and ½ in. wide (Figure 1). The forewing of adults is gray-colored with black spots, and the legs are black-colored. The head is black with a pair of short, orange-colored antennae. The forewing completely covers the hindwing. The tip of the hindwing is black (Figure 8). White and black bands are present toward the abdomen. The lower region of the hindwing is red-colored with black spots. The wingspan is about 2.2 in.

Photo: Lawrence Barringer, Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture, Bugwood.org.

The abdomen is yellow-colored with black stripes in the center. Adults are often found in masses in “hot” trees (Figure 9). Some adjacent trees may have no adults at all.

Photo: Lawrence Barringer, Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture, Bugwood.org.

Dispersal

The spotted lanternfly’s egg-laying behavior—being able to lay egg masses on any substrate—helps them to disperse quickly in the late fall and winter to new areas. The hitchhiked eggs laid on rail cars, trailer trucks, recreational vehicles, or campers find new habitats in the following year when they hatch (Figure 10).

Still images from video “Here’s what to do when you see spotted lanternfly eggs,” by Chelsea Johnson, March 27, 2022, Fox43 News (https://www.fox43.com/article/sports/outdoors/spotted-lanternfly-eggs-heres-what-to-do-pennsylvania/521-1dce1724-8708-4645-a108-e808b793e41c).

They have successfully adapted to new host plants in new locations. It’s good practice to look for SLF egg masses on vehicles and materials originating from their established areas to delay their establishment in new places. When detected, the egg masses can be physically destroyed by stomping or other means.

Host Plant Range

Photo: Jan Samanek, Phytosanitary Administration, Bugwood.org.

Spotted lanternflies feed on more than 103 tree species; however, not all hosts support the development of nymphs. In northern states, the tree of heaven (Ailanthus altissima; Figure 11) is considered a key host species that helps them develop and reproduce profusely. Some tree species do not support reproduction or development of nymphs as females fail to produce eggs and, in some instances, nymphs do not develop into adults. Nymphs move and feed on multiple tree species. Food hosts other than tree of heaven include red maple (Acer rubrum), silver maple (Acer saccharinum), black walnut (Juglans nigra), butternut (Juglans cinerea), river birch (Betula nigra), rose (Rosa spp.), staghorn sumac (Rhus typhina), weeping willow (Salix babylonica), wild grape (Vitis spp.), and wine grape (Vitis vinifera).

Maples and grapes, including muscadine grapes, are common in north and central Georgia and South Carolina. It is not clear how tree hosts in the South will influence establishment and population dynamics of spotted lanterfly. Maples are widely planted in urban areas, including parks, residential areas, and commercial sites. Similarly, wild grapes (including muscadine grapes) are typical in wooded areas.

Monitoring

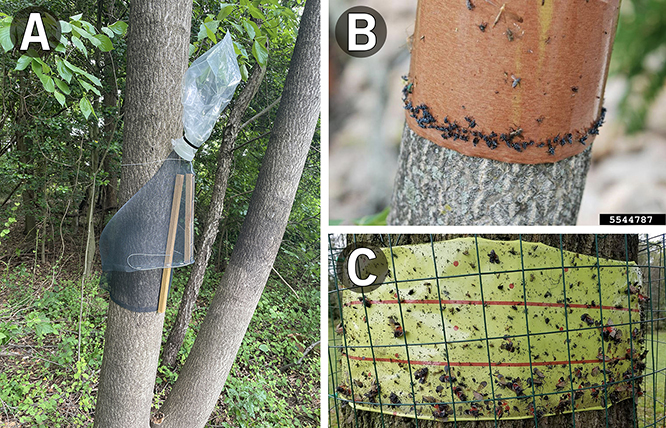

Photos: (A) From “Spotted lanternfly,” by Fairfax County (Virginia) Public Works and Environmental Services, 2023 (https://www.fairfaxcounty.gov/publicworks/trees/spotted-lanternfly); (B) Lawrence Barringer, Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture, Bugwood.org; (C) From “Spotted lanternfly management,” by New York State Integrated Pest Management, Cornell University (https://cals.cornell.edu/new-york-state-integrated-pest-management/outreach-education/whats-bugging-you/spotted-lanternfly/spotted-lanternfly-management).

SLF adults and nymphs can be monitored using circle traps, sticky traps, jar traps, etc. Sticky traps will also attract other insects and birds. Traps should be monitored at regular intervals (once in 7 or 14 days). These traps are effective when deployed on susceptible tree hosts, such as tree of heaven. These traps provide information on the life stages present at a given time and estimate population size.

Circle Traps

To make a circle trap, a metal mesh funnel is attached to a tree trunk to direct spotted lanternflies into a collection container or bag (Figure 12A). Those SLF entering the collection container or bag are trapped inside. A commercially purchased methyl salicylate lure can be used within the collection container or bag to attract the spotted lanternflies. Methyl salicylate lures usually are replaced monthly.

Sticky Traps

A sticky trap is created by wrapping sticky tape around a tree trunk (Figure 12B). A metal guard or mesh is used to cover the sticky tape to prevent birds and other vertebrates from sticking (Figure 12C).

Lampshade Traps

Egg masses can be monitored using lampshade traps. Construction of the lampshade trap is described in Lampshade Trap Construction for Spotted Lanternfly Egg Masses (Lewis, 2022), which is linked in the References section.

Spotted Lanternfly Management

Spotted lanternfly feeding rarely causes measurable injury to trees. However, extensive populations that cause sooty mold developed on the honeydew produced by SLF can be a nuisance. This can also reduce the aesthetic value of the affected trees.

Spotted lanternfly infestation is managed using insecticides. Tree injection, bark sprays, or soil drenches are effective methods of delivery of systemic insecticides, such as neonicotinoids. The best time to apply imidacloprid is from May to July. If dinotefuran is used, the best timing is from July to September.

Pyrethroids, such as beta-cyfluthrin, bifenthrin, and zeta-cypermethrin, and reduced-risk insecticides, such as neem oil, horticultural and dormant oils, and insecticidal soap, are effective on adults and nymphs. The residual activity of reduced-risk insecticides is very short compared to pyrethroids and neonicotinoids. Because insecticide exposure can affect pollinators and other nontarget organisms, insecticides should be used cautiously.

Spotted lanternflies are susceptible to biological control agents, such as praying mantis or spiders, but predator activity is not high enough to suppress the SLF population. Beauveria bassiana strains are effective on spotted lanternfly adults and nymphs.

References

Barringer, L., & Ciafré, C. M. (2020). Worldwide feeding host plants of spotted lanternfly, with significant additions from North America. Environ. Entomol., 49(5), 999–1011. https://doi.org/10.1093/ee/nvaa093

Clifton, E. H., Castrillo, L. A., Gryganskyi, A., & Hajek, A. E. (2019). A pair of native fungal pathogens drives the decline of a new invasive herbivore. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 116(19), 199178–80. http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1903579116

Lewis, P. A. (2022). Lampshade trap construction for spotted lanternfly egg masses. USDA-APHIS Forest Pest Methods Laboratory. https://ag.umass.edu/sites/ag.umass.edu/files/pdf%2Cdoc%2Cppt/lampshade_trap_for_slf_egg_masses_lewis_2022.pdf

Simisky, T., Piñero, J., Barnes, E., Orth, J. F., & LaScola-Miner, T. (2022). Spotted lanternfly management. UMass Extension Landscape, Nursery, and Urban Forestry Program. https://ag.umass.edu/landscape/fact-sheets/spotted-lanternfly-management

Urban, J. M. (2020). Perspective: shedding light on spotted lanternfly impacts in the USA. Pest Manag. Sci., 76(1), 10–17. https://doi.org/10.1002/ps.5619